In Finland, our narrator – is it Bujar? Is it Agim? – meets Tanja, who is transitioning from male to female, and hearing her story he ponders to himself: In the Albanian folktales Bujar’s father tells him, changes of persona are key – life is a series of transitions. Does the fact that in the present day the narrator isn’t named suggest that it is Agim and not Bujar who is telling us this part of the tale?

And it is Agim who, from an early age, presents as female. Most importantly, sometimes he presents as a woman, sometimes as a man.īack in Tirana, however, it is Agim, not Bujar, who has the talent for assuming new identities, who, for example, takes the lead when the pair claim to be related to a powerful gangster in order to buy a boat to cross the Adriatic. Sometimes he’s Italian sometimes Spanish, and once, Turkish. This same narrator offers each new person he meets in the West a different account of where he comes from, who he is. This is my greatest quality, the game of dress up that I can start and stop whenever it suits me.’ ‘I am a man who cannot be a woman but who can sometimes look like a woman.

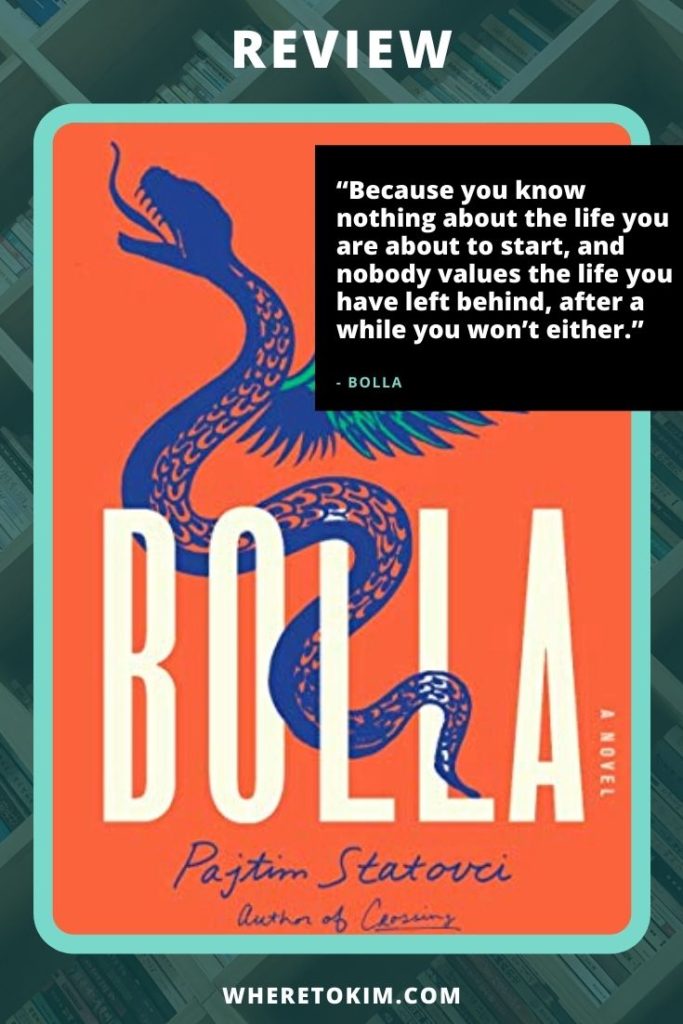

In the very first chapter – an extract from which is published alongside this review – we find the narrator dissembling: Doubt begins to creep in, however, about the true identity of our narrator. At the heart of this assured and subtle novel is a mystery about identity – that of the protagonist and more broadly that of each of us, as queer people, straight people, Europeans and non-Europeans, as immigrants and as indigenous people.įollowing the lives of two queer Albanians as they escape their home country to make new lives for themselves in the West, the first impression is that the novel is told from the first-person point of view of Bujar, who relates two parallel narrative threads: one tracing past events in Tirana as he and best friend Agim grow up and then start to plan their escape the other following our narrator as he travels to Rome, Madrid, New York and Helsinki.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)